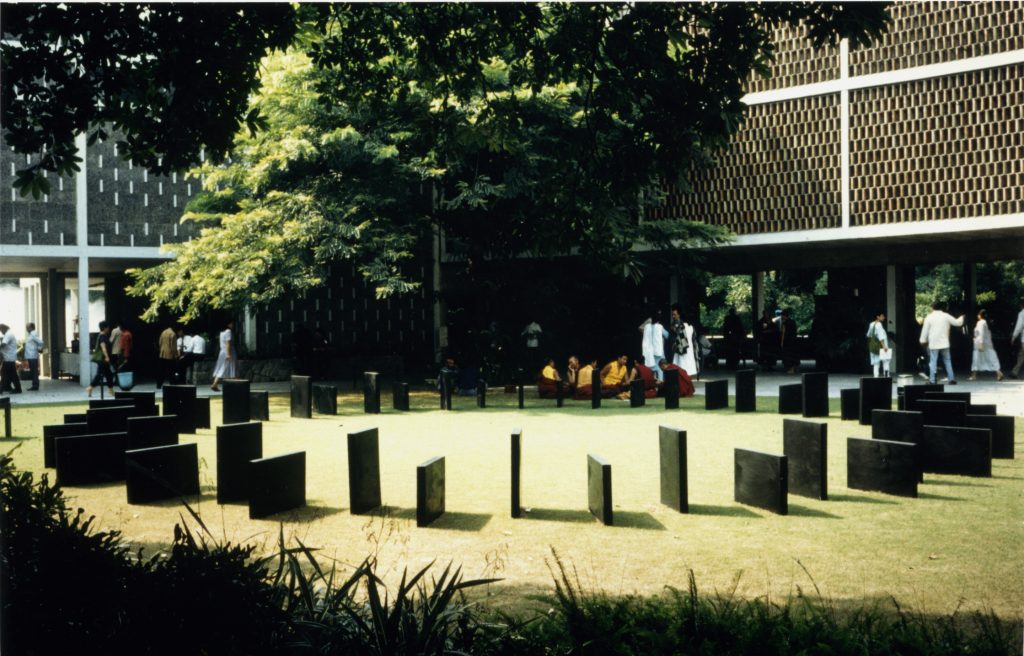

ATHANASY – The Fire Consuming Otherness, HELLA BERENT 1993 India International Center and Tibet House, New Delhi, India

Interview with Hella Berent by Jari Chevalier

recorded on October 3, 1993 at India International Art Center, New Delhi

JC: How did you come up with the title of the work?

HB: Athanasy represents the fire-consuming otherness.

JC: What does that mean?

HB: You know, I very much appreciate the French writer, poet, and philosopher George Bataille, who died in the 1960s. In his writings, we find the idea for the need of waste. In the material life we have no possibility to get in touch with something that would be the truth. Wounds are covered with skin, you’ve to go inside and beyond to find out, and then this coating, you’ve to go beyond it in a sense – this is what you find in Bataille’s writings. His book Thanatography is the opposite of Athanasy. Thanatos means death; Athanasy is being imperishable, the condition of everlasting life, of the fire-consuming otherness. I’ve had so many thoughts about difference, about polarity and about unity. And through all these thoughts I arrived at this title.

JC: I caught these themes just by looking at the work. One notices divisions – horizontals and verticals, highs and lows, space and shadows, and there is time in there because it looks a bit like the divisions on a clock reminding me of stone ranges and sundials. All of this is coming across very clearly.

HB: Yeah.

JC: And time and space are things that are imperishable, at least from our perspective, the imperishable things.

HB: Yeah, but that’s all quite relative. I mean, I wouldn’t have said that time and space are imperishable, because I see the title Athanasy more in relation to the human being, to being itself. This installation is related to Buddhism: the 49 pieces indicate the different states between death and rebirth. I picked that up from the Tibetan Book of the Dead. I was so fascinated by the description that there might be an in-between state that actually lasts 49 days and is called Bardo. Each stone of the installation represents one state in this development; so there is time per se.

JC: So are you saying that this entire circle is taking place in the period between death and rebirth.

HB: The measurements of the stones result from the play of numbers; the 49 is the result of 7 times 7, and the measurement is 49 cm, 7 cm by 7 cm, just an easy relation, one could take any size and do the same.

JC: The same ratio. How do these abstractions relate to you in your human life, on the level of the heart?

HB: You know, all these thoughts, approaches, the choice of materials – all these things have a long history in my work; they relate to my heart in the way that all decisions I take come out of my own life path, out of my experience. Thinking about polarity and the desire to overcome it, I see the only possibility is to walk through the mirror. My feeling is that there is always something in-between, which is socially not defined that gives space to find relations because existence can’t just be black or white, good or bad.

JC: It’s as if you’re finding meaning to your struggle to release yourself from polarity in the fact that you see this struggle as not just personal but rather as universal on a cosmic level.

HB: Yes. Regarding the installation I must mention that there are 48 stones in the circle and one, the 49th stone, is lying on the table. And this separation seems to be a symmetry although it isn’t, because the 49th stone is separate and points to another level of symbolic being, namely the essence of being itself. It’s the essence of what is going around, so that it isn’t just a circle as form but on a more abstract level the thing in itself.

JC: But you know that…

HB: That the whole is the one and the one is the whole.

JC: You know that one stone on the table really adds a thought-provoking dimension to the entire work. And it could be interpreted as that the circle represents the way things are and the single stone represents what human beings make of it, almost like laying the Book of Life on the table.

HB: That’s nice to hear because for me it is important that it is play, an object given in public to be seen as a phenomenon and the recipient can enter it with his or her own being.

JC: That’s the whole idea of art.

HB: That’s great.

JC: To elevate consciousness.

HB: And so you have the vertical and the horizontal and the circle, and the horizontal text in relation to the vertical positions, and finally on the line out there is the second table.

JC: Is that part of the same installation?

HB: Yes, it is.

JC: Oh, I wasn’t sure if that was a whole other work of art or whether it was meant to be part of this work.

HB: Yes, you know installation means to take the volume of the space and set new positions so that the volume is reactivated in a different way than it has been used before.

JC: And so we have this rubber book of flexible black pages. But there is also some white on them, a kind of dust. And it is bound, that seems important.

HB: Yes, that is important.

JC: It’s like a book that you could see anything written in, by reversal, white on black. And what about the solid white gloves?

HB: Those are actually for the viewer to wear. To protect the rubber, you know, and to keep that white.

JC: Yes, people have oily fingers and the likes. I thought the gloves were part of the symbolism and were just meant to be sitting there. And I thought it was great that they are dirtied.

[The recording is disrupted here and picks up somewhere on the following page.]

HB: I couldn’t decide that before, I knew about the display but not how to realize it. And when I came here [to India} and saw the 33 steps and the environment, I knew immediately that I had to use stones. Then I looked for materials. I didn’t want to use marble or granite and then found this black Cuddapah stone, which on the surface has a great resemblance to rubber.

JC: It does! I could see it in the sun. You know yesterday when you had the opening it was dusk. But this morning when I came over here for breakfast, I saw completely different things in the installation. First of all I could see your…

HB: The stones and how they were worked on.

JC: Yes, and each one different and interesting. And because it was early in the morning, the sun was low in the sky and there were all these long shadows.

HB: Yeah! I have to come in the morning and take photographs.

JC: Do you give much thought to the role or value of the artist in society? Considering that this is an ecological conference, what do you see that artists can do regarding world problems and the crisis we’re in?

HB: I can see only one central possibility and that is to sensibilize people.

JC: Sensibilize – meaning have people become more sensible.

HB: More sensitive and more trust in the capacity of their own senses. To explore while being face to face with phenomena. Phenomena are not combined with news, obviously, so people can start thinking and feeling.

JC: Be stimulated.

HB: I can’t offer practical advice.

JC: I think that’s what artists have always done. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to be in proportion to the power of the consumer society.

HB: Though I wonder sometimes, when political regimes are changing and for instance in South America, in Chile, where a new dictator, Pinochet, took power it is at first the artists – singers, writers, painters and sculptors, photographers – who are being discriminated. It is amazing that generally speaking society is never aware of the importance of the arts, especially when systems are changing.

JC: The artists are the first to go.

HB: The first who get censored. Society is always fearful when art becomes subversive. That’s the power of art.

JC: The subtler the subversion…

HB: Then it gets devoured. The strength and freedom of art is to move with something that is life. This strength is revealed in more subversive artworks.

JC: It’s good to hear you say this because I think people could view your work as very cerebral and the fact that it is black and spacious may appear cold. Yet you are talking about warmth, you’re talking about movement, there’s nothing static in it, it’s about growth. Yet your colors, your images are abstract. So where is the meeting point between that.

HB: You’ve to know a little about aesthetics when you move the pages of the book, when the sun moves the shadows of the pieces, there is so much of that.

JC: Yes, personally, I am moved by the way you speak. But the general public is often very critical of contemporary art as being abstract and removed. They want something pretty and colorful.

HB: To recognize yourself in it straightaway. When there is a tulip on the table at home, they want to see the tulip.

JC: Comfortable…

HB: Yes, relieved and feeling at home and all that. You don’t have to worry, to think about it. But you need some energy to get into it, but that’s life!

JC: So rather than to be stroked and confirmed…

HB: And mirrorized! Same thing in painting, colorful, wonderful, beautifully painted, you can just be quiet and calm and you don’t have to bother.

JC: We are right back where we started with breaking through the mirror.